Member-only story

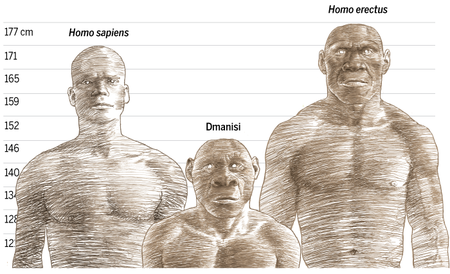

Robusticity, as measured by a ratio of bone thickness to bone length, is fundamentally determined by biomechanical stress and the presence of androgens. There is a cline of less robusticity as one goes across the various species of Homo (H. Erectus had the most muscle, H. Sapiens has the least).

Early Modern Homo Sapiens had more robust arms and legs than us today, simply because they walked more, and perhaps on rugged and hilly terrain. They were also engaging in throwing activities (first the boomerang, then the atlatl), which has a certain effect on the humeral head and femur. Domestic activities such as scraping and flintknapping would also have an effect on upper arm strength.

Both early humans (before 100 kya) and Neanderthals seem to have been running even more than today’s marathon runners (ScienceDirect). This same pattern, interestingly, is seen in Khoi San people, who are known to run after animals for hours after being speared or shot with an arrow. Tracking is likely the reason for running in these ancient humans.

Australian Hunter-Gatherers, representative of EMHS. Maybe you have seen the picture before. They are lean, not overly muscular, but one can see they lead physically tough lives.

Neanderthals had much more robust humeri and radii than Early Modern H. Sapiens. While there have been studies showing scraping could account for the bone morphologies in Neanderthals, it is likely that the high multi-directional forces generated by wrestling animals down could have also done the trick. That and a high exposure to animal products (including their androgens, fat, and protein) could have amplified the effect.

It is also more than likely that Neanderthals had very sensitive androgen receptors, judging from their early age of puberty and general masculine features, such as massive brow ridges. Thus, the docking of testosterone to the androgen receptor would be more efficient.